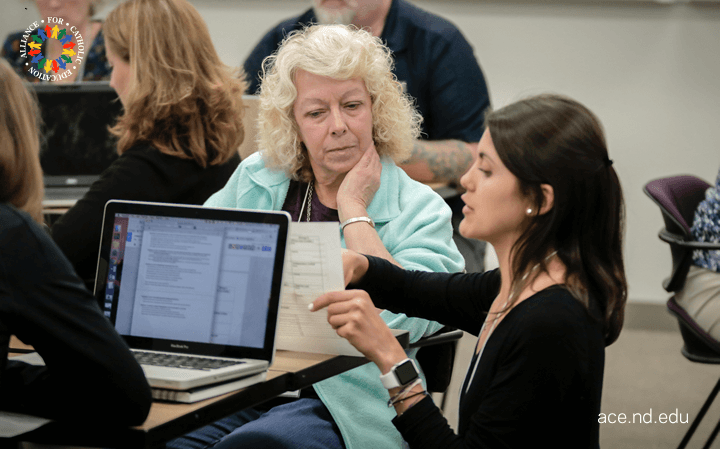

I recently had the privilege of joining my colleagues from the Notre Dame Center for STEM Education for the third annual RISE Summit in Palo Alto, California. The RISE Summit is an opportunity for Trustey Family STEM Teaching Fellows–some of the nation's most outstanding STEM teachers who take part in a multiyear professional development program through the Center–to gather, reflect, collaborate, and grow. As if a trip to California in January was not enough on its own, I was overjoyed by the enthusiasm, curiosity, and determination of the 56 Fellows. I learned so much from these outstanding teachers throughout our short workshop on blended learning, and I wanted to share one of the most important takeaways and one of the most interesting discussions from our session.

A takeaway: Blended learning can be an extremely impactful model when employed correctly.

We addressed many misconceptions about blended learning during our workshop, which helped us all understand situations when blended learning doesn't work as we hoped. But we also realized that we can adjust the blended-learning models we use to impact our students in a positive way. Here's what the Trustey Fellows had to say about this:

"I thought I was doing [blended learning], but I was doing it wrong. I can and should be getting much more data about my students."

"I learned how I could use [blended learning] to help my students be more 'in charge' of their own learning"

"I learned the power of the rotation (from station to station). Each part has a purpose in the learning process." (See our previous post on protecting purpose in the blended classroom for more on this subject).

And finally, my favorite question of the day, "I learned about the value of integrating technology with personal instruction to help students realize their full potential. Why is this model of learning not standard across the nation?"

This last quote reinforces something Fr. Nate and I like to tell anyone who will listen: in a few years, this will no longer be called "blended learning," it will simply be called "learning."

An Interesting Discussion: How can we prevent tracking in blended learning?

Given the Trustey Fellows' emphasis on equity and providing meaningful and rigorous learning experiences for all students, I was not the least bit surprised that the issue of tracking arose in our discussion–but that doesn't mean that I had an easy answer.

Many people are leery of grouping students based on academic performance, and rightly so. This strategy, called tracking, often results in students being tagged as lower-performing or "slow" from a young age and never having the opportunity to break free of this label. This is particular concerning for students from minority or low socioeconomic status populations who often begin school trailing their peers from wealthier families – if these students start in the "slow" group, some argue that they may never have a real chance to advance.

When we discussed the popular rotational model of blended learning, a number of the Trustey Fellows expressed concern that splitting the students into performance-based groups at a young age may lead to tracking, which would be detrimental to the students over the long term. We obviously want to avoid this in our classrooms, so we ask two things of our teachers:

- Regularly change performance-based groups based on student data and the lesson objectives. Students are constantly learning and advancing, so performance-based groups should never remain static for longer than a few weeks at a time. Furthermore, students' readiness and mastery varies by the objective at hand, and teachers should vary their groups accordingly. For example, leveled groups may be very different for a geometry standard than for a numbers and operations standard. The beauty of blended learning is that it gives teachers the data they need to make these adjustments and ensure that students are not pigeon-holed as low-performing.

- Use mixed groups. Performance-based groups can be very effective, but they are not always necessary. For certain lessons, teachers should try grouping students of different academic levels together. In addition to preventing students from being tied to a specific leveled group, this will allow students to work with peers who have different skills and levels of mastery, who challenge and teach one another, and who practice valuable leadership and collaboration skills.

If teachers employ both of these strategies, we believe that blended-learning programs will allow students to realize their full potential regardless of the level at which they start. The Trustey Fellows were excited about these suggestions, and we hope you will be, too!

The Trustey Fellows left the weekend excited to experiment with blended learning and put some of these ideas into practice. If you have any suggestions for this awesome group, we would love to learn from you! Let us know in the comments below!

Interested in learning more about the Trustey Family STEM Teaching Fellows? Visit stemeducation.nd.edu/trustey and submit your application before March 1!

Alliance for Catholic Education

Alliance for Catholic Education