Hilary Murphy, a graduate of the SJCHS Benilde Program, recently earned a Master of Education degree in school counseling.

Hilary Murphy would beg to differ with the assumption that, until very recently, Catholic K-12 schools struggled to offer students with learning differences the resources they need to succeed. Challenges tied to attention issues, reading comprehension, or academic-related health concerns were passed along to public schools, according to conventional wisdom. But Murphy recalls her student days at St. John’s College High School in Washington, D.C., from 2001 to 2005, as a life-changing time of respect and responsiveness for her and unique obstacles she faced.

“I was diagnosed with a learning disability” as an adolescent, Murphy said, but St. John’s, a Lasallian Christian Brothers school for motivated teens with college goals, placed her in an innovative grouping called the Benilde Program. Established a few years earlier by a laywoman and named after a 19th century Lasallian educator, St. Benilde (Ben-ild) Romancon, the program taught her how to manage tasks successfully given her learning style. Specialists raised awareness of needs and solutions, and all teachers understood how they could offer Benilde students accommodations without changing the rigorous curriculum and culture of the St. John’s community.

Responsibilities for identifying problems and solutions resided largely with the Benilde students. But they learned “valuable life skills,” such as how to study for a test, take notes, stay organized, and manage time and stress, Murphy said. “All of those skills were especially useful when I went to college and graduate schools.” Benilde-specific classes offering special academic support did not pull students out of the mainstream college-prep courses. Murphy recalled the bonus of friendships in “a community of students whom you connected with easily because you shared similar experiences, struggles and successes."

A growing number of Catholic K-12 schools are implementing programs that welcome a wider range of students with learning differences. These educators continue to combine innovations with traditional values from the heart of a school’s Catholic identity, including hospitality, kindness, and accountability.

The Benilde Program, which has been implemented formally in more than a dozen high schools and takes different forms and names in additional schools around the country, incorporates a number of De La Salle Christian Brothers and Catholic school values, said Brother Michael Andrejko, F.S.C., principal of St. John’s College High School.

He highlighted the dignity of every individual, the importance of meeting and serving every unique person where he or she is in life, the impact of caring relationships between teachers and students, and a religious community’s respectful collaboration with lay leaders.

St. John’s reflected the latter value 17 years ago when it turned to a laywoman, Doreen Engel, to be the founding director of the foresighted Benilde Program that changed Hilary Murphy’s school experience.

“I had a major interest in seeing what Catholic schools could do to be more welcoming and inclusive,” Engel said in a recent interview. She has been a champion for inclusive education in several leadership settings since she established and directed the St. John’s program. Engel currently leads the new Benilde initiative at St. Raphael Academy, a Christian Brothers school in Pawtucket, RI. Various Lasallian Christian Brothers schools and others have adopted elements of the initiative under different names. A range of additional programs exist, marked by still sharper differences, for serving children with learning exceptionalities.

Engel said the spread of the Benilde initiative provides further proof that Catholic schools are more eager and better equipped than ever to serve young people with challenges ranging from ADHD to test-taking skills and the organization of tasks.

Seventeen years ago, administrators at St. John’s instinctively shared Engel’s desire for greater outreach. Recognizing her expertise in special-needs education, they supported her ambition to design the new program named for St. Benilde, whom a pope once praised for a perseverance that “enabled him to do common things in an uncommon way.”

The program appropriately reflects a lot of the common sense and uncommon insights embraced in Catholic schools, Engel said. She rejects some schools’ current inclination simply to add on services customized for students who fit pre-defined categories of need. Benilde’s “new paradigm” broadly assesses how a school’s operating procedures might be tailored to meet the needs of all students.

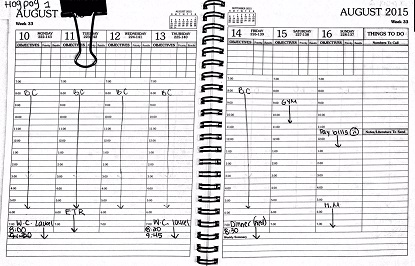

Eileen O’Toole, the most recent Benilde director at St. John’s, said students in the program have special timeslots in their schedules to tap Benilde resources, but otherwise they attend the same classes, have the same instructional goals, and use the same materials, including iPads. Many of them gain insights and skills allowing their Benilde support system to end before their senior year, Brother Andrejko noted.

Accommodations to students’ basic similarities and to unique personal traits—such as extended time or other arrangements for some test-takers—can bring the student and teacher communities closer together, according to Engel. Modifications for individuals, always based on psychological evaluations and recommendations, might involve class schedules, teaching styles, and assistance with note-taking. Ongoing dialogues among Benilde staff and students’ regular-course teachers monitor the modifications.

Accommodations to students’ basic similarities and to unique personal traits—such as extended time or other arrangements for some test-takers—can bring the student and teacher communities closer together, according to Engel. Modifications for individuals, always based on psychological evaluations and recommendations, might involve class schedules, teaching styles, and assistance with note-taking. Ongoing dialogues among Benilde staff and students’ regular-course teachers monitor the modifications.

The collaborations, structures, and shared commitments of such a program may also encourage continuous innovations in a school, through technology and other means, an exceptional-learning teacher noted.

Catholic schools’ emphasis on personal dignity leads the Benilde program to help students and their parents “de-mystify” their learning experiences, added Engel. Students and the community benefit when they understand how their challenges can evoke cooperation, not detachment.

Furthermore, Brother Andrejko explained, Benilde emphasizes each person’s accountability for becoming fully themselves. A Catholic school should be accessible to everyone, especially the poor and the marginalized, he said, but expectations are high, too: “You’re responsible for your education. You accept ownership of it and your responsibility to become men and women for others, taking your God-given gifts and using them in service to others.”

A focus on others means giving students the knowledge and self-confidence to approach teachers and other authority figures, explaining the special circumstances and suggesting cooperation and modifications to create a win-win situation, Brother Andrejko said.

“We teach the students to advocate for themselves, to speak up to get the extra help they need,” he said. St. John’s works hard to make sure every one of the 100 Benilde students—and every one in the entire 1,100-student population—receive individual attention: “We take the student as a whole person.”

This commitment demands investments of time, effort, and money by multiple parties. Different schools facing different demographics must decide for themselves how much to invest and how to adapt aspects of the Benilde program, according to those who know the program.

At St. John’s, a tuition add-on for those who make it through the rigorous screening process into the program provides an experienced Benilde staff leader. Educators and counselors with special-needs training, along with supplemental course time and extensive coordination within the school’s whole team, help students every day.

O’Toole, said elements of the program are useful for—and are being adapted by—more and more Catholic schools. Elementary and secondary schools—in the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, often located in underserved communities—adjust according to their own abilities. They share a commitment to welcome as many students as possible, from all backgrounds.

“Benilde is distinctively Catholic, but it’s up to every school to decide implementation for themselves,” said O’Toole, who studied educational psychology at Catholic University of America. She has seen under-resourced K-12 schools “do all sorts of ingenious things” to maximize the resources for students with special learning challenges, thanks to the commitment of school communities’ leaders and educators.

O’Toole played a crucial role in advancing the inclusionary vision by compiling a “Philosophy of Education” document. It outlines the Benilde program in light of previous guidelines for Catholic schools from the U.S. bishops.

The goal is to develop students as “self-reflective, independent problems solvers,” the benchmark document states. “Lasallian education gives the student a basic education and understanding of Christ so the student can go out and share his gifts,” O’Toole wrote.

Alliance for Catholic Education

Alliance for Catholic Education