“We continue to go to the outskirts,” David Faber says, highlighting the call of Pope Francis to nurture young people’s faith and reach out to serve at the periphery.

Surrounded by its rural landscape, the Diocese of Grand Rapids has identified parishes stretched to afford operating their schools and developed a new technology-focused initiative, called WINGS, in order to build efficiencies that will enrich those communities over the long term.

Faber, superintendent of schools for the diocese, says the innovation of WINGS can avoid closure of local schools—and empower both their teachers and students—through a system of “satellite sites” governed jointly as one school, with multiple-grade classrooms adapted to smaller student populations and, a heavy dose of 21st century technology.

The initial proposal of these solutions struck some people as an overly sharp move from traditional structures, but this was deemed to be the best hope for the local schools and students. Unlike many of the modernizations taking place in K-12 schools, the innovation is not in an “at-risk neighborhood,” but amid the farmlands and apple orchards north and west of Grand Rapids.

In 2010, Faber proposed an alternative to the “consolidation” that was needed to address the financial strain at St. Michael (Coopersville), St. Catherine (Ravenna), and St. Joseph (Conklin). Parishioners loved sending their children to a local Catholic school, but the parishes could neither justify serving tiny student populations nor increase those enrollments through new demographic outreach. It appeared two of the schools would have to close.

Faber won then-Bishop Walter Hurley’s approval for a bold alternative that relatively few Catholic schools—or public schools—had adopted. The local buildings would stay open, still supported by the parishioners, but these would be satellites of a single school—eventually christened Divine Providence Academy, with combined governance under one director, Kendra DeYoung.

Two members of the separate parish school boards helped lay the groundwork for this 21st century model and called it WINGS, standing for world knowledge; individualized, innovative education; a nurturing family environment; God-centered; and supportive technology. The model combines shared governance and multi-age classrooms with blended learning.

One year after the launch of WINGS, DeYoung came on-board and showed unique insight in implementing the vision.

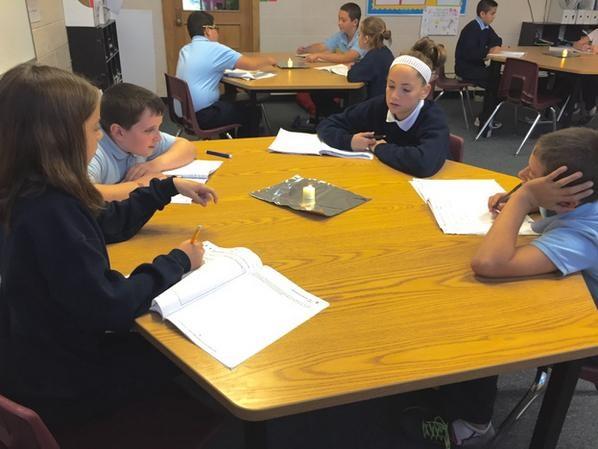

Individualized education arose partly from investing to integrate computers, software, and systems for managing data about student performance. Teachers continue to be the sine qua non in each classroom, treating every student with individual dignity and, with help from blended learning experts, fine-tuning their instruction to each student’s personal progress.

Faber saw two advantages. Teachers could focus more closely on forming each student at the right level, so the typical structure of “first-grade classrooms,” separate from “second-grade classrooms,” became moot. Inefficiencies of separating teachers for each grade, no matter how small, disappeared.

“This just-right learning empowered teachers because their coaching was guided by each student’s independent growth portfolio,” says Faber.

Students, better able to take ownership of their learning, pushed ahead with enthusiasm. Standardized tests now show strong achievement gains. Nearly five years later, Divine Providence Academy leads the diocese in students’ academic growth.

A shift toward multi-age classrooms seemed revolutionary to some, but it’s nothing new in light of one-room schoolhouses that many parents and grandparents grew up with.

No one’s saying the transition to multi-age classrooms, shared governance, and right-sized schools with satellite units is easy. One of the three parish schools originally participating in Divine Providence Academy dropped out, preferring to offer local pre-K classes only.

Trust in the innovation is only now starting to prove itself. Besides the impressive student data, this model has dramatically cut the participating parishes’ contributions to the school and overall school expenses by about 10 percent. Parishes using WINGS can retain their local school property, relationships, and community influence, an affirmation of the principle of subsidiarity found in Catholic social teaching.

Other dioceses have shown interest in adopting this alternative to school closures, consolidations, and infusions of benefactor funding. Of course, no model works for all schools and situations. Nor is this only a “rural” option. Faber hopes the diocese’s current strategic planning process leads various communities to embrace the concept.

Updates of conventional approaches to learning add to Catholic schools’ tool kit to solve today’s challenges in America’s diverse education scene.

“This provides a small-school model that’s supportable and sustainable,” Faber says, “and it’s an instructional model where the kids are growing faster than in any of our other schools.”

Alliance for Catholic Education

Alliance for Catholic Education