As I glare down through the musty fog, a galaxy of crystals forged in the granite countertop captivates my mind’s eye. Even 15 minutes after I had opened the rusted, earthy Writing Handbook, its flaked debris swarms like a sandstorm inadvertently forging a veil between myself and its prescriptions. I seek out anything and everything to divert my attention from the words below.

In nomenclature known only within certain classrooms of my high school, my grammatical errors are noted in red. My directive: “Revise your errors using the Writing Handbook by 1. Transcribing the grammatical rules at hand using the Handbook and 2. Correcting those errors using those aforementioned rules.” My motivation: nonexistent.

Instead, I craft alternate universes using the landscape surrounding the text, only occasionally adventuring too close to the illuminating heat lamp above. The purpose of these adventures to the sun are twofold. First, touching the fiery bulb provides needed, grounding comparison to the torturous task of revision. Second, these zaps serve as the sole igniter of my energy to complete the mundane and tedious burden at hand.

I no longer ask “why”; I just do.

This brief attempt at creative writing serves to illustrate my experience with learning grammar via “prescriptive” and “formal” modes of grammar instruction. I still remember that thick, brown Writing Handbook that in a former time could have been used as a means of corporal punishment, but instead found its function serving as an (arguably more painful) pedagogical practice: constraining writing revision. Throughout my high school experience, many long hours were spent copying down seemingly archaic and useless rules from this handbook, and the only residual fruit of this labor manifested in knowledge of trivial grammatical structures.

This experience, alongside the widespread social discourse concerning grammar instruction, turned me away from recognizing the value of understanding grammar itself. It wasn’t until my undergraduate experience that I started thinking more critically about how to manipulate the normative structure of language for the sake of creating and enhancing meaning. Through various tests and trials of grammatical constructions, I began to recognize more fully the incredible power that language and its structure possesses.

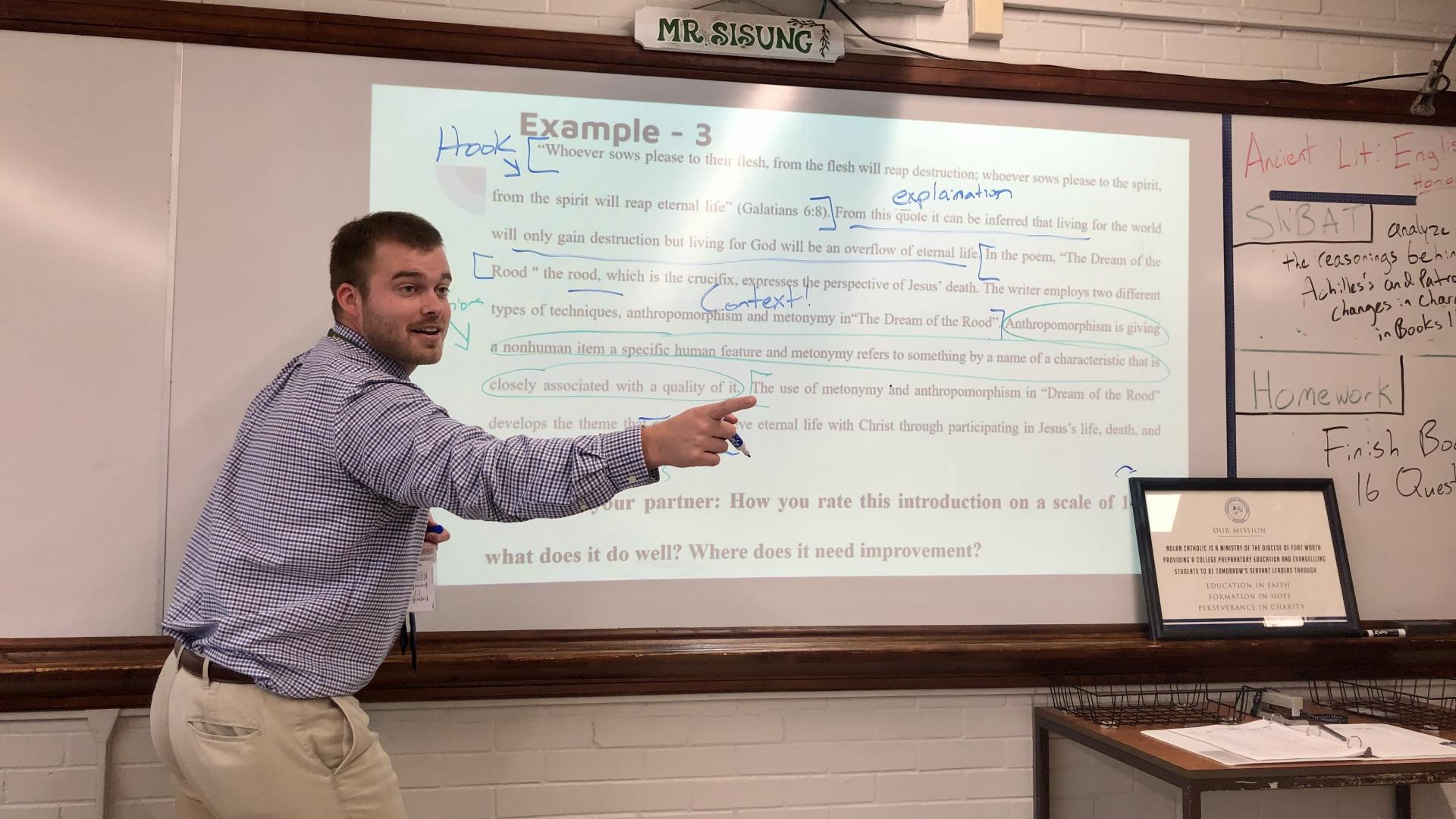

Now, as a high school language arts teacher, I am tasked with teaching grammar. During my first year of teaching, I placed little emphasis on grammar instruction – I was still navigating the ropes of teaching the English language. In my second year, the value and importance of teaching grammar have become ever so clear.

My approach to teaching grammar aligns most closely with Martha Kolln’s (1995) concept of “rhetorical” grammar. This approach to teaching grammar focuses upon developing students’ ability to use grammar as a rhetorical tool so that writers are able to make intentional grammatical decisions while conscious of those decisions’ rhetorical effects. In this manner, students are taught both the function and the purpose of each aspect of language and language construction both individually and in relation to one another.

My desire to develop my grammar instruction grew recently during a brief meeting with one of my sophomores who asked if I could help her revise her writing assignment. In reviewing that assignment, my first suggestion was that she substitute her current verb choices with stronger and more dynamic verbs in order to elevate the delivery of her central claims. To this advice, she responded, “But, Mr. Sisung, I do not know what a verb is.” Following this encounter, I polled my students by having them put their heads down on the desk and raise their hands if they agreed with the following statement: “I’ve heard of the word “verb,” and I know that verbs are used in sentences, but I do not really know what a “verb” is.” To this statement, roughly 60% of my sophomore students raised their hands. This informal polling is certainly not proper data collection, but it does provide some insight into the fact that many of my students (and I would argue that this data is representative of high school students generally) do not possess a foundational understanding of the purposeor construction of language.

Thus, teaching “rhetorical” grammar has become a focus in my classroom. My goal is to teach my students the functions of the foundational building blocks of the English language so that they can best understand their purpose and effect both as writers and readers. A recent mini-lesson that employed this practice was inspired by that original question about verbs from one of my students. In this lesson, I prompted students to discuss the different rhetorical effects of similarly constructed passages whose main variants were the verb choices. For example, I had students discuss the different rhetorical effects of a statement like “I ate the cake” versus a statement like “I devoured the cake.” While each of these statements convey the same action, the latter’s meaning is more nuanced than the former.

This mini-example illustrates the power and purpose of teaching rhetorical grammar. Equipped with the skills to critically analyze the language they write and read, students are more able to authentically recognize themselves, others, and the world around them. In this manner, teaching rhetorical grammar provides our students with the means to liberate themselves from the constraints of language. Further, students are better able to take their knowledge of language and assert their voices forcefully and effectively into our world. Thus, instead of causing students to lose themselves in the various worlds constructed during daydreams, we can provide them with the tools to develop their own galaxies of language through rhetorical grammar instruction

Alliance for Catholic Education

Alliance for Catholic Education